- Home

- Ronald Purser

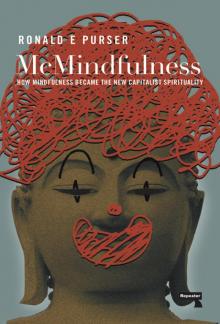

McMindfulness

McMindfulness Read online

McMindfulness

How Mindfulness Became the

New Capitalist Spirituality

McMindfulness

How Mindfulness Became the

New Capitalist Spirituality

RONALD E. PURSER

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE:

What Mindfulness Revolution?

CHAPTER TWO:

Neoliberal Mindfulness

CHAPTER THREE:

The Mantra of Stress

CHAPTER FOUR:

Privatizing Mindfulness

CHAPTER FIVE:

Colonizing Mindfulness

CHAPTER SIX:

Mindfulness as Social Amnesia

CHAPTER SEVEN:

Mindfulness’ Truthiness Problem

CHAPTER EIGHT:

Mindful Employees

CHAPTER NINE:

Mindful Merchants

CHAPTER TEN:

Mindful Elites

CHAPTER ELEVEN:

Mindful Schools

CHAPTER TWELVE:

Mindful Warriors

CHAPTER THIRTEEN:

Mindful Politics

CONCLUSION:

Liberating Mindfulness

NOTES

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

chapter one

What Mindfulness Revolution?

Mindfulness is mainstream, endorsed by celebrities like Oprah Winfrey, Goldie Hawn and Ruby Wax. While meditation coaches, monks and neuroscientists rub shoulders with CEOs at the World Economic Forum in Davos, the founders of this movement have grown evangelical. Prophesying that its hybrid of science and meditative discipline “has the potential to ignite a universal or global renaissance,” the inventor of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), Jon Kabat-Zinn, has bigger ambitions than conquering stress. Mindfulness, he proclaims, “may actually be the only promise the species and the planet have for making it through the next couple hundred years.”1

So, what exactly is this magic panacea? In 2014, Time magazine put a youthful blonde woman on its cover, blissing out above the words: “The Mindful Revolution.” The accompanying feature described a signature scene from the standardized course teaching MBSR: eating a raisin very slowly indeed. “The ability to focus for a few minutes on a single raisin isn’t silly if the skills it requires are the keys to surviving and succeeding in the 21st century,” the author explained.2

I am skeptical. Anything that offers success in our unjust society without trying to change it is not revolutionary — it just helps people cope. However, it could also be making things worse. Instead of encouraging radical action, it says the causes of suffering are disproportionately inside us, not in the political and economic frameworks that shape how we live. And yet mindfulness zealots believe that paying closer attention to the present moment without passing judgment has the revolutionary power to transform the whole world. It’s magical thinking on steroids.

Don’t get me wrong. There are certainly worthy dimensions to mindfulness practice. Tuning out mental rumination does help reduce stress, as well as chronic anxiety and many other maladies. Becoming more aware of automatic reactions can make people calmer and potentially kinder. Most of the promoters of mindfulness are nice, and having personally met many of them, including the leaders of the movement, I have no doubt that their hearts are in the right place. But that isn’t the issue here. The problem is the product they’re selling, and how it’s been packaged. Mindfulness is nothing more than basic concentration training. Although derived from Buddhism, it’s been stripped of the teachings on ethics that accompanied it, as well as the liberating aim of dissolving attachment to a false sense of self while enacting compassion for all other beings.

What remains is a tool of self-discipline, disguised as self-help. Instead of setting practitioners free, it helps them adjust to the very conditions that caused their problems. A truly revolutionary movement would seek to overturn this dysfunctional system, but mindfulness only serves to reinforce its destructive logic. The neoliberal order has imposed itself by stealth in the past few decades, widening inequality in pursuit of corporate wealth. People are expected to adapt to what this model demands of them. Stress has been pathologized and privatized, and the burden of managing it outsourced to individuals. Hence the peddlers of mindfulness step in to save the day.

But none of this means that mindfulness ought to be banned, or that anyone who finds it useful is deluded. Its proponents tend to cast critics who hold such views as malevolent cranks. Reducing suffering is a noble aim and it should be encouraged. But to do this effectively, teachers of mindfulness need to acknowledge that personal stress also has societal causes. By failing to address collective suffering, and systemic change that might remove it, they rob mindfulness of its real revolutionary potential, reducing it to something banal that keeps people focused on themselves.

A Private Freedom

The fundamental message of the mindfulness movement is that the underlying cause of dissatisfaction and distress is in our heads. By failing to pay attention to what actually happens in each moment, we get lost in regrets about the past and fears for the future, which make us unhappy. The man often labeled the father of modern mindfulness, Jon Kabat-Zinn, calls this a “thinking disease.”3 Learning to focus turns down the volume on circular thought, so Kabat-Zinn’s diagnosis is that our “entire society is suffering from attention deficit disorder — big time.”4 Other sources of cultural malaise are not discussed. The only mention of the word “capitalist” in Kabat-Zinn’s book Coming to Our Senses: Healing Ourselves and the World Through Mindfulness occurs in an anecdote about a stressed investor who says:

“We all suffer a kind of A.D.D.”5

Mindfulness advocates, perhaps unwittingly, are providing support for the status quo. Rather than discussing how attention is monetized and manipulated by corporations such as Google, Facebook, Twitter and Apple, they locate the crisis in our minds. It is not the nature of the capitalist system that is inherently problematic; rather, it is the failure of individuals to be mindful and resilient in a precarious and uncertain economy. Then they sell us solutions that make us contented mindful capitalists.

The political naiveté involved is stunning. The revolution being touted occurs not through protests and collective struggle but in the heads of atomized individuals. “It is not the revolution of the desperate or disenfranchised in society,” notes Chris Goto-Jones, a scholarly critic of the movement’s ideas, “but rather a ‘peaceful revolution’ being led by white, middle class Americans.”6

The goals are unclear, beyond peace of mind in our own private worlds.

By practicing mindfulness, individual freedom is supposedly found within “pure awareness,” undistracted by external corrupting influences. All we need to do is to close our eyes and watch our breath. And that’s the crux of the supposed revolution: the world is slowly changed — one mindful individual at a time. This political philosophy is oddly reminiscent of George W. Bush’s “compassionate conservatism.” With the retreat to the private sphere, mindfulness becomes a religion of the self. The idea of a public sphere is being eroded, and any trickle-down effect of compassion is by chance. As a result, notes the political theorist Wendy Brown, “the body politic ceases to be a body, but is, rather, a group of individual entrepreneurs and consumers.”7

Mindfulness, like positive psychology and the broader happiness industry, has depoliticized and privatized stress. If we are unhappy about being unemployed, losing our health insurance, and seeing our children incur massive debt through college loans, it is our responsibility to learn to be more mindful. Jon Kabat-Zinn assures us that “happiness is an inside job” that simply requires us to attend to the present moment mindfully and purposely without judgment.8 Anot

her vocal promoter of meditative practice, the neuroscientist Richard Davidson, contends that “wellbeing is a skill” that can be trained, like working out one’s biceps at the gym.9 The so-called mindfulness revolution meekly accepts the dictates of the marketplace. Guided by a therapeutic ethos aimed at enhancing the mental and emotional resilience of individuals, it endorses neoliberal assumptions that everyone is free to choose their responses, manage negative emotions, and “flourish” through various modes of self-care. Framing what they offer in this way, most teachers of mindfulness rule out a curriculum that critically engages with causes of suffering in the structures of power and economic systems of capitalist society.

If this version of mindfulness had a mantra, its adherents would be chanting “I, me and mine.” As my colleague C.W. Huntington observes, the first question most Westerners ask when considering the practice is: “What is in it for me?”10

Mindfulness is sold and marketed as a vehicle for personal gain and gratification. Self-optimization is the name of the game. I want to reduce my stress. I want to enhance my concentration. I want to improve my productivity and performance. One invests in mindfulness as one would invest in a stock hoping to receive a handsome dividend. Another fellow skeptic, David Forbes, sums this up in his book Mindfulness and Its Discontents:

Which self wants to be de-stressed and happy? Mine! The Minefulness Industrial Complex wants to help your self be happy, promote your personal brand — and of course make and take some bucks (yours and mine) along the way. The simple premise is that by practicing mindfulness, by being more mindful, you will be happy, regardless of what thoughts and feelings you have, or your actions in the world.11

Of course, this is a reflection of capitalist norms, which distort many things in the modern world. However, the mindfulness movement actively embraces them, dismissing critics who ask if it really needs to be this way.

The Commodification of Mindfulness

Mindfulness is such a well-known commodity that it has even been used by the fast-food giant KFC to sell chicken pot pies. Developed by a high-powered ad agency, KFC’s “Comfort Zone: A Pot Pie-Based Meditation System” uses a soothing voiceover and mystical images of a rotating Col Sanders sitting in the lotus posture with a pot pie head. The video “takes listeners on a journey,” says the narrator: “The Comfort Zone is a groundbreaking system of personal meditation, mindfulness and affirmation based on the incredible power of KFC’s signature pot pie.”12

Mindfulness is now said to be a $4 billion industry, propped up by media hype and slick marketing by the movement’s elites. More than 100,000 books for sale on Amazon have a variant of “mindfulness” in their title, touting the benefits of Mindful Parenting, Mindful Eating, Mindful Teaching, Mindful Therapy, Mindful Leadership, Mindful Finance, a Mindful Nation, and Mindful Dog Owners, to name just a few. There is also The Mindfulness Coloring Book, a bestselling subgenre in itself. Besides books, there are workshops, online courses, glossy magazines, documentary films, smartphone apps, bells, cushions, bracelets, beauty products and other paraphernalia, as well as a lucrative and burgeoning conference circuit. Mindfulness programs have made their way into public schools, Wall Street and Silicon Valley corporations, law firms, and government agencies including the US military. Almost daily, the media cite scientific studies reporting the numerous health benefits of mindfulness and the transformative effects of this simple practice on the brain.

Branding mindfulness with the veneer of hard science is a surefire way to get public attention. A key selling and marketing point for mindfulness programs is that it has been proven that meditation “works” based on the “latest neuroscience.” But this is far from the case. As many prominent contemplative neuroscientists admit, the science of mindfulness and other forms of meditative practice is in its infancy and understanding of brain changes due to meditation has been characterized as trivial.13 “Public enthusiasm is outpacing scientific evidence,” says Brown University researcher Willoughby Britton. “People are finding support for what they believe rather than what the data is actually saying.”14 The guiding ethos of scientific research is to be disinterested and cautious, yet when studies are employed for advocacy, their trustworthiness becomes suspect. “Experimenter allegiance,” Britton worries, “can count for a larger effect than the treatment itself.” There is a great deal of momentum in the mindfulness movement to override the caution that is the hallmark of good science. Together, researchers seeking grant money, authors seeking book contracts, mindfulness instructors seeking clients, and workshop entrepreneurs seeking audiences have talked up an industry built on dubious claims of scientific legitimacy.

Another marketing hook is the distant connection to Buddhist teachings, from which mindfulness is excised. Modern pundits have no qualms about flaunting this link for its cultural cachet — capitalizing on the exoticness of Buddhism and the appeal of such icons as the Dalai Lama — while at the same time dismissing Buddhist religion as foreign “cultural baggage” that needs to be purged. Their talking points frequently claim that they offer “Buddhist meditation without the Buddhism,” or “the benefits of Buddhism without all the mumbo jumbo.” Leaving aside the insulting tone, to which most seem oblivious (although it’s the same as saying: “I really like secular Jews without all the Jewishness… you know, all the beliefs, rituals, institutions, and cultural heritage of Judaism — all that mumbo jumbo…”), they are stuck in a colonial mode of discourse. They lay claim to the authentic essence of Buddhism for branding prestige, while declaring that science now super-sedes Buddhism, providing access to a universal understanding of mindfulness.

Some Buddhist responses make challenging points. To quote Bhikkhu Bodhi, an outspoken American monk, the power of meditative teachings might enslave us: “Absent a sharp social critique,” he warns, “Buddhist practices could easily be used to justify and stabilize the status quo, becoming a reinforcement of consumer capitalism.”15 While I could argue whether mindfulness is a Buddhist practice or not (spoiler alert: it’s not), that would only distract from what is really at stake.

As a management professor and a longstanding Buddhist practitioner, I felt a moral duty to start speaking out when large corporations with questionable ethics and dismal track records in corporate social responsibility began introducing mindfulness programs as a method of performance enhancement. In 2013, I published an article with David Loy in the Huffington Post that called into question the efficacy, ethics and narrow interests of mindfulness programs.16 To our surprise, what we wrote went viral, perhaps helped by the title: “Beyond McMindfulness.”

The term “McMindfulness” was coined by Miles Neale, a Buddhist teacher and psychotherapist, who described “a feeding frenzy of spiritual practices that provide immediate nutrition but no long-term sustenance.”17 Although this label is apt, it has deeper connotations. The contemporary mindfulness fad is the entrepreneurial equal of McDonald’s. The founder of the latter, Ray Kroc, created the fast food industry. Like the mindfulness maestro Jon Kabat-Zinn, a spiritual salesman on par with Eckhart Tolle and Deepak Chopra, Kroc was a visionary. Very early on, when selling milkshakes, Kroc saw the franchising potential of a restaurant chain in San Bernadino, California. He made a deal to serve as the franchising agent for the McDonald brothers. Soon afterwards, he bought them out, and grew the chain into a global empire. Inspiration struck Kabat-Zinn after earning his doctorate in molecular biology at MIT. A dedicated meditator, he had a sudden vision in the midst of a retreat: he could adapt Buddhist teachings and practices to help hospital patients deal with physical pain, stress and anxiety. His masterstroke was the branding of mindfulness as a secular crypto-Buddhist spirituality.

Both Kroc and Kabat-Zinn had a remarkable capacity for opportunity recognition: the ability to perceive an untapped market need, create new openings for business, and perceive innovative ways of delivering products and services. Kroc saw his chance to provide busy Americans instant access to food that would be delivered consiste

ntly through automation, standardization and discipline. He recruited ambitious and driven franchise owners, sending them to his training course at “Hamburger University” in Elk Grove, Illinois. Franchisees would earn certificates in “Hamburgerology with a Minor in French Fries.” Kroc continued to expand the reach of McDonald’s by identifying new markets that would be drawn to fast food at bargain prices.

Similarly, Kabat-Zinn perceived the opportunity to give stressed-out Americans easy access to MBSR through a short eight-week mindfulness course for stress reduction that would be taught consistently using a standardized curriculum. MBSR teachers would gain certification by attending programs at Kabat-Zinn’s Center for Mindfulness in Worcester, Massachusetts. He continued to expand the reach of MBSR by identifying new markets such as corporations, schools, government and the military, and endorsing other forms of “mindfulness-based interventions” (MBIs). As entrepreneurs, both men took measures to ensure that their products would not vary in quality or content across franchises. Burgers and fries at McDonald’s are predictably the same whether one is eating them in Dubai or in Dubuque. Similarly, there is little variation in the content, structuring and curriculum of MBSR courses around the world.

Since the publication of “Beyond McMindfulness,” I have observed with great trepidation how mindfulness has been oversold and commodified, reduced to a technique for just about any instrumental purpose. It can give inner-city kids a calming time-out, or hedge fund traders a mental edge, or reduce the stress of military drone pilots. Void of a moral compass or ethical commitments, unmoored from a vision of the social good, the commodification of mindfulness keeps it anchored in the ethos of the market.

A Capitalist Spirituality

This has come about partly because proponents of mindfulness believe that the practice is apolitical, and so the avoidance of moral inquiry and the reluctance to consider a vision of the social good are intertwined. Laissez-faire mindfulness lets dominant systems decide such questions as “the good.” It is simply assumed that ethical behavior will arise “naturally” from practice and the teacher’s “embodiment” of soft-spoken niceness, or through the happenstance of inductive self-discovery. However, the claim that major ethical changes intrinsically follow from “paying attention to the present moment, non-judgmentally” is patently flawed. The emphasis on “nonjudg-mental awareness” can just as easily disable one’s moral intelligence. It is unlikely that the Pentagon would invest in mindfulness if more mindful soldiers refused en masse to go to war.

McMindfulness

McMindfulness